The human mind is the greatest, most complex and mysterious concept in the universe. And quantum mechanics, the most astonishing, perplexing, and hard-to-understand field of science, found some of its principles opposed even by Albert Einstein. Scientists now are trying to apply quantum mechanical principles to the human brain to explain the human consciousness and mind and their relation with matter.

Quantum mechanics developed as an attempt to explain discrepancies observed in experiments that could not be explained by classical theory. Scientists hoped that it would help them understand human consciousness, since, in a parallel manner, behaviorism could not explain adequately the complex structure of human behavior.

The intersection of physics, psychology, and biology led to a new pseudo scientific field: quantum consciousness. Although some say it is nothing more than a fantasy,(1) others have found the concepts offered by quantum mechanics to be useful.

Classical physics cannot explain the human consciousness and mind.(2) Newton's well-established laws of mechanics posited a deterministic universe. In short, he stated that if every detail of a system were known at a particular time, its future state could be predicted precisely. As classical physics perceives the universe as consisting of objects and fields, and requires nothing further to explain the systems, there is no place for such concepts as consciousness and mind. Materialistic theories generally based on the classical approach do not deny the mind's existence; they just say is has no effective action on the brain.(3)

Quantum Mechanics

What basic principles of new physics allow the mind to control matter? Quantum mechanics was an unnoticed revolution. Set in a probabilistic world, it changed the whole idea of a deterministic universe. Unlike classical physics, quantum mechanics cannot talk of future events with complete certainty; it can only evaluate the probability that a certain event will occur. The Uncertainty Principle, which prevents a precise and simultaneous determination of a particle's velocity and position, means that all trajectories assigned by Newtonian mechanics to describe the resulting motion are invalid.

In a quantum world, waves are associated with particles. These probability waves carry all information about a given quantum object. At this point, the probability function says nothing about the particle's actual movement and state. Such an observation requires a measurement.

However, this means collapsing the wave function into one of the probable results. When such a measurement is made, the particle will be found in one of the probable states. Thus one cannot know the system's actual state either between observations or in the future. This is why determinism collapsed and the universe became a collection of probable events. Even Einstein denied the concept of such a bizarre and perplexing result: "God does not play dice!"

How do scientists use quantum mechanic tools to study consciousness? Do they really explain how the brain works and the subtle relation between consciousness and matter?

Are Mind and Matter Somehow Related?

The mind-matter connection remains one of the greatest unsolved mysteries. It requires a comprehensive approach featuring a deep understanding of how the brain functions, physical laws, and human psychology. Although there are different approaches, the main problems are how to explain this connection scientifically and how to close the gap between the brain's material structure and the tremendous results of its functioning.

Since the time of Descartes (d. 1650), one general approach has been to treat the mind and brain separately by placing them in different categories. One model based on this duality involves finding a parallelism between a computer's hardware and software and the human mind and brain, respectively.

This is not the only approach, however. The materialist idea, based on the deterministic universe model, focuses on the brain's functioning and either disregards mind and consciousness or supposes them to be illusory. For decades, this view had a great impact on theories related to the brain and mind. Minsky's approach of "minds are simply what brains do" reflects quite literally this approach.(4)

On the other hand, the natural occurrence of necessity for a mind or a soul, as a result of a quantum mechanic view of the brain, to have control over matter seems to cause a change in both evolutionary and materialistic models of conscious thought. This was a direct consequence of applying quantum mechanics to chemical reactions occurring in the atomic world of neurons.

Indeed, some claimed that various processes in living bodies required a quantum mechanic treatment. For example, light-sensitive cells in a human eye (in a retina, which is considered part of the brain) are sensitive to even one photon that is truly a quantum particle.(5) Eccles, a neurophysiologist famous for his contributions to neuroscience, discusses quantum effects in synaptic action and claims that some functional parts of neurons need to be treated as quantum sites.(6)

The materialistic view taught that when brain cell interactions were understood completely, nonmaterial concepts would become unnecessary. Interactions between neurons are now said to cause conscious thought. Therefore, neuroscience focuses on explaining brain cell (neuron) interactions.

The Role of Neurons

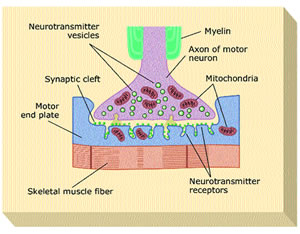

Neurons are connected to each other by their strands (axons and dendrites) across synapses (Figure 1). Electrical signals are carried by neurotransmitters located in synaptic gaps (Figure 2). The release of neurotransmitters is initiated by calcium ions entering the synapses from the fluid surrounding the cell. Calcium cations cross into the cell through calcium channels.

Stapp treats calcium channels as the area in which quantum consciousness can be applied, and where the effect of the mind comes into play. Diffusing a small calcium cation (a positively charged ion) through the calcium channel cannot be treated as a classical phenomenon, for in a classical diffusion each particle follows a certain trajectory through the channel. But when considered from a quantum view, the particle (or cation), starting from one end of the channel to the other end, takes all possible paths at the same time. Only a measurement can locate the particle in one of the channel's possible paths [collapse of state into one of the probable events]. Therefore, one path becomes real. In a real transmission, since there is no measurement, the mind chooses the path, which supports the theory that matter can be controlled by the mind. Since the chosen trajectory will either enhance or decrease the probability of neurotransmitter release, the whole communication process will be affected. Due to this probabilistic nature of events, the mind should control the brain.(7) Sir John C. Eccles, a British neurophysiologist and Nobel Prize winner for his work on how neurons communicate with each other, is an important contributor to the mind-brain interaction issue. He focuses on microsites where synaptic vesicles (little bags of neurotransmitters) are released. (The figurative structure of a synapse is shown in Figure 2.) He claims that the process taking place in those microsites is a quantal emission (a release of multimolecular packets). In the synapse of two neurons, vesicles are stored in certain places and released according to electrical impulses. Eccles emphasizes that the mind (or mental events) does not initiate any activity in those synapses; rather, he hypothesizes that mental events control only the probability of each vesicle's release from the microsites. In this model, he agrees with Margenau, who also says there are such things as nonmaterial events(8): "The mind may be regarded as a field in the accepted physical sense of the term. But it is a nonmaterial field; its closest analogue is perhaps a probability field. It cannot be compared with the simpler nonmaterial fields that require the presence of matter (hydrodynamic flow or acoustic)…Nor does it necessarily have a definite position in space. And so far as present evidence goes it is not an energy field in any physical sense, nor is it required to contain energy in order to account for all known phenomenon which mind interacts with brain." According to Eccles, microsites are targets for such nonmaterial mental events as an intention to carry out some movement. Pointing out that vesicles are released without any energy input, the mind's effect on them is seen in the form of an increased probability of neurotransmitter release. Eccles, who believes in the soul, supports the dualist approach starting from self-consciousness and the unity of self. In his How the Self Controls Its Brain, he summarizes his approach with a quotation from Hodgson(9): "What we are looking for, I think, is a purpose that we should try to recognize and pursue, which our lives if correctly lived will fulfill in fact, and which is right and good. It may also be God's purpose for us. I think that the notion of a purpose of life makes more sense in relation to a God, or some wider consciousness, than it otherwise would." Victor J. Stenger, a proponent of the materialistic view, summarizes the materialists' general idea of quantum consciousness theories: "The myth of quantum consciousness should take its place along with gods, unicorns, and dragons as yet another product of the fantasies of people unwilling to accept what science, reason, and their own eyes tell them about the world." A comparison of points made by Eccles and Stenger shows that science cannot be independent of the thoughts of those who establish it. This is why quantum consciousness theories remain controversial.

Stapp treats calcium channels as the area in which quantum consciousness can be applied, and where the effect of the mind comes into play. Diffusing a small calcium cation (a positively charged ion) through the calcium channel cannot be treated as a classical phenomenon, for in a classical diffusion each particle follows a certain trajectory through the channel. But when considered from a quantum view, the particle (or cation), starting from one end of the channel to the other end, takes all possible paths at the same time. Only a measurement can locate the particle in one of the channel's possible paths [collapse of state into one of the probable events]. Therefore, one path becomes real. In a real transmission, since there is no measurement, the mind chooses the path, which supports the theory that matter can be controlled by the mind. Since the chosen trajectory will either enhance or decrease the probability of neurotransmitter release, the whole communication process will be affected. Due to this probabilistic nature of events, the mind should control the brain.(7) Sir John C. Eccles, a British neurophysiologist and Nobel Prize winner for his work on how neurons communicate with each other, is an important contributor to the mind-brain interaction issue. He focuses on microsites where synaptic vesicles (little bags of neurotransmitters) are released. (The figurative structure of a synapse is shown in Figure 2.) He claims that the process taking place in those microsites is a quantal emission (a release of multimolecular packets). In the synapse of two neurons, vesicles are stored in certain places and released according to electrical impulses. Eccles emphasizes that the mind (or mental events) does not initiate any activity in those synapses; rather, he hypothesizes that mental events control only the probability of each vesicle's release from the microsites. In this model, he agrees with Margenau, who also says there are such things as nonmaterial events(8): "The mind may be regarded as a field in the accepted physical sense of the term. But it is a nonmaterial field; its closest analogue is perhaps a probability field. It cannot be compared with the simpler nonmaterial fields that require the presence of matter (hydrodynamic flow or acoustic)…Nor does it necessarily have a definite position in space. And so far as present evidence goes it is not an energy field in any physical sense, nor is it required to contain energy in order to account for all known phenomenon which mind interacts with brain." According to Eccles, microsites are targets for such nonmaterial mental events as an intention to carry out some movement. Pointing out that vesicles are released without any energy input, the mind's effect on them is seen in the form of an increased probability of neurotransmitter release. Eccles, who believes in the soul, supports the dualist approach starting from self-consciousness and the unity of self. In his How the Self Controls Its Brain, he summarizes his approach with a quotation from Hodgson(9): "What we are looking for, I think, is a purpose that we should try to recognize and pursue, which our lives if correctly lived will fulfill in fact, and which is right and good. It may also be God's purpose for us. I think that the notion of a purpose of life makes more sense in relation to a God, or some wider consciousness, than it otherwise would." Victor J. Stenger, a proponent of the materialistic view, summarizes the materialists' general idea of quantum consciousness theories: "The myth of quantum consciousness should take its place along with gods, unicorns, and dragons as yet another product of the fantasies of people unwilling to accept what science, reason, and their own eyes tell them about the world." A comparison of points made by Eccles and Stenger shows that science cannot be independent of the thoughts of those who establish it. This is why quantum consciousness theories remain controversial.

Conclusion

Despite the ongoing controversy over quantum mechanics, quantum consciousness is an important first step toward explaining how the mind might control matter. Solving the mind-brain issue could revolutionize neuroscience and artificial intelligence. A better understanding of quantum mechanics and its applications to neuroscience might help scientists solve the mind-matter puzzle. However, we should keep in mind that: "I think that is safe to say that no one understands quantum mechanics. Do not keep saying to yourself, if you can possibly avoid it 'But how can it be like that?' because you will go 'down the drain' into a blind alley from which nobody has yet escaped. Nobody knows how it can be like that." (Richard Feynman)

Footnotes

1 Victor J. Stenger, "The Myth of Quantum Consciousness," The Humanist 53, no. 3 (May-June 1992): 13-15. 2 Henry P. Stapp, Mind, Matter and Quantum Mechanics, part 1 (Germany: Springer-Verlag, 1993), 37. 3 C. John Eccles, How the Self Controls Its Brain (Germany: Springer-Verlag: 1994), 4. 4 Nick Herbert, Elemental Mind, Human Consciousness and the New Physics (New York: Dutton, 1993), 116. 5 Roger Penrose, Shadows of the Mind: A Research for the Missing Science of Consciousness (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), 349. 6 Eccles, How the Self Controls Its Brain. 7 Herbert, Elemental Mind, 258. 8 Eccles, How the Self Controls Its Brain, 73. 9 ibid, 39.

References (not cited in article)

- Davies, Paul, Other Worlds, (Simon and Schuster, New York, 1980), p.17-35.

- Eccles, C. John, How the Self Controls its Brain, (Springer-Verlag, Germany, 1994).

- Herbert, Nick, Elemental Mind, Human Consciousness and the New Physics, (Dutton, New York, 1993), Chap. 4,10.

- Hodgson, David, The Mind Matter: Consciousness and Choice in a Quantum World, (Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1991), p.47, Part IV.

- Penrose, Roger, Shadows of the Mind, A Research for the Missing Science of Consciousness, (Oxford University Press, New York, 1994), chap. 7.

- Stapp, Henry P., Mind, Matter and Quantum Mechanics, (Springer-Verlag, Germany, 1993), Part I, p.79-116.

- Stenger, Victor J., "The Myth of Quantum Consciousness," The Humanist, May/June 1992, Vol. 53, Number 3, p.13-15.